sehr langer Artikel, hier das Ende:

....The Way It Ends

If Japan continues to run large budget deficits, as is likely, then the falling saving rate and reversal in its current account will make it more difficult for the government to borrow, at least at current low rates.

Ignoring foreign borrowing and debt monetization by the central bank,

the stock of private sector savings limits the amount of government debt. In the case of Japan, this equates to around 250-300% of GDP. Japan"s gross government debt will reach this level around 2015, although net government debt will not reach this limit until after 2020.

Even before Japan"s government debt exceed household"s financial assets, the declining savings rate and increasing drawing on savings by aging households will reduce inflows into JGBs (Japan-Bonds, A.L.), making domestic funding of the deficit more difficult.

Insurance companies and pension funds are increasingly selling their holdings or reducing purchases to fund the increase in payouts to people eligible for retirement benefits. Institutional investors -- and, to a lesser extent, retail investors -- are also increasingly investing in other assets, including foreign securities, in an effort to increase returns and diversify their portfolios.

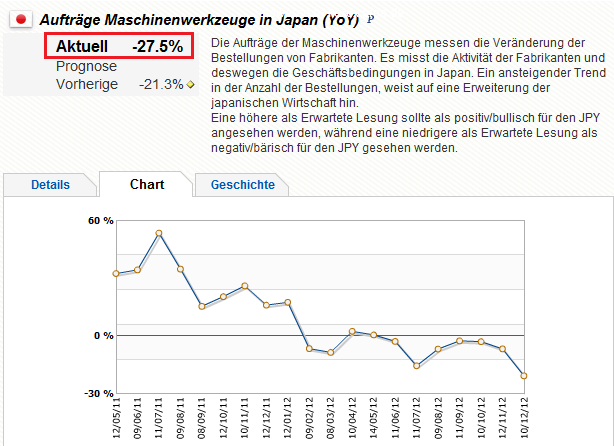

Forecast current account deficits will complicate the government"s financing task. Japan"s large merchandise trade surplus has shrunk and will remain under pressure reflecting weak export demand and high imported energy costs. (siehe Grafik unten, A.L.)

Japan"s large portfolio of foreign assets will cushion the effects for a time. Japan has accumulated large foreign assets totalling around US$4 trillion, making it the world's biggest net international creditor. The BoJ is the largest investor in US Treasury bonds, with holdings of around US$1 trillion. But even if net income from foreign assets (interest payments, profits, and dividends) stays constant, Japan"s overall current account may move into deficit as soon as 2015.

As the drawdown on financial assets to finance retirement accelerates, Japan will initially run down its overseas investments, losing its net foreign asset position. Unless public finances improve, Japan ultimately will be forced to finance its budget deficit by borrowing overseas.

Where the marginal buyers of JGBs are foreign investors rather than domestic Japanese investors, interest rates may increase, perhaps significantly. Even at current low interest rates, Japan spends around 25-30% of its tax revenues on interest payments. At borrowing costs of 2.50% to 3.50% per annum, two to three times current rates, Japan"s interest payments will be an unsustainable proportion of tax receipts. [Diese Gefahr droht allen Ländern, die massiv QE betreiben - und zwar in dem Moment, wenn die künstlich gesenkten Zinsen wieder anziehen, A.L.]

Higher interest rates will also trigger problems for Japanese banks, Japanese pension funds, and insurance companies, which also have large holdings of JGBs.

JGBs total around 24% of all bank assets, which is expected to rise to 30% by 2017. An increase in JGB yields would result in immediate mark-to-market large losses on existing holdings, although higher returns would boost income longer term. BoJ estimates that a 1% rise in rates would cause losses of US$43 billion for major banks, equivalent to 10% of Tier 1 Capital for major banks or 20% for regional banks.

To avoid the identified chain of events, Japan must address the core problems. But reductions in the budget deficit are difficult. Spending on social security accounts and interest expense now totals a major part of government spending. Increasing health and aged care costs are expected by 2025 to be around 10-12% of GDP. An aging population and shrinking workforce will continue to drive slower growth and lower tax revenues. Tax increases are politically unpopular. Reductions in the budget deficit are likely to reduce already weak economic activity, compounding the problems.

Japanese policymakers have other options. Financial repression forcing investment in low interest JGBs is one alternative. The BoJ can maintain its zero rate policy and monetize debt to finance the government. Japan can try to inflate away their debt. But ultimately, Japan may have no option other than a domestic default to reduce its debt levels.

Cassandra Does Japan

Investors and traders have repeatedly bet on a Japanese crisis, usually by short selling JGBs to benefit from higher rates. With low Japanese interest rates, the risk of the trade has always seemed limited while the potential profit large. But the bet has failed each time, giving the strategy its name – the "widow maker."

Given its large domestic savings and also the ability of the BoJ to further monetize its debt, the status quo can be maintained for a little longer. But eventually Japan"s deteriorating public finances and declining ability to finance itself domestically will coincide with weakening ratings and large refinancing needs.

Japan"s toxic combination of weak economic performance, large budget deficits, high and increasing levels of government debt, declining household savings, and looming current account deficits is increasingly unsustainable. Once the problems emerge, they will be difficult to contain. As economist Rudiger Dornbush once observed: "The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought."

www.minyanville.com/sectors/global-markets/...2013/id/47354?page=full

(Verkleinert auf 91%)