The chart below presents the top 20 sovereigns with the largest amount of net CDS (not gross) notional outstanding. Interestingly, Italy and Spain, with their $20.4 billion and $11.1 billion in net notional, have the most net risk exposure, (General Electric, parent of brutally realistic and objective financial news station CNBC is at $11.2 billion). Additionally, the chart demonstrates not just the current spread of any given sovereign's CDS level, but also the phenomenal tightening that has occurred since March 6. What is surprising, is that as corporate risk has been socialized by sovereigns all over the world (most notably in the US).P.S. the missing country name on the chart below is Ireland. ......

Antworten | Börsen-Forum Übersicht

... 1732 1733 1735 1736 ...

Der USA Bären-Thread

Passende Knock-Outs auf DAX

| Strategie | Hebel | |||

| Steigender DAX-Kurs | 5,00 | 10,03 | 19,97 | |

| Fallender DAX-Kurs | 5,44 | 9,99 | 19,99 | |

Zugriffe: 26.385.842 / Heute: 703

|

The chart below presents the top 20 sovereigns with the largest amount of net CDS (not gross) notional outstanding. Interestingly, Italy and Spain, with their $20.4 billion and $11.1 billion in net notional, have the most net risk exposure, (General Electric, parent of brutally realistic and objective financial news station CNBC is at $11.2 billion). Additionally, the chart demonstrates not just the current spread of any given sovereign's CDS level, but also the phenomenal tightening that has occurred since March 6. What is surprising, is that as corporate risk has been socialized by sovereigns all over the world (most notably in the US).P.S. the missing country name on the chart below is Ireland. ......

.....the man who knows most about AIG’s troubles lives in a stucco-fronted house in London. Some call him Patient Zero: the virus that infected the world financial system was transmitted from a genteel square near Harrods. If you wait patiently in Knights-bridge you will see him, and he appears not to be a risk-taking type. He puts on his red crash helmet and cycles greenly off across the city, politely declining to comment on global calamities. This does not look like a person waiting at the curtains for the arrival of the FBI.

Can one man in London really be to blame for the collapse of capitalism?

Until now, the economic crisis has been seen as a giant intellectual error, and AIG’s multimillionaire employees in England were simply the people who made the biggest mistakes. The first to own up to misjudgment was Gordon Brown’s friend Alan Greenspan — once so revered in his role as America’s central banker that to be photographed with him was as flattering as being seen now with President Obama. “I have found a flaw,” said Greenspan, referring to his free-market philosophy, after the banks started falling over. “I don’t know how significant or permanent it is. But I have been very distressed by that fact.”.....

...The official version is that Joseph Cassano, who occupies the stucco-fronted house near Harrods, brought down a safe and stable company — and by extension, the world — with incompetent gambles. “You’ve got a company, AIG, which used to be just a regular old insurance company,” Obama explained during a recent TV appearance. “Then they decided — some smart person decided — let’s put a hedge fund on top of the insurance comp-any, and let’s sell these derivative products to banks all around the world.” Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, adds: “This was a hedge fund, basically, that was attached to a large and stable insurance company.”

Cassano, who ran AIG’s financial-products division in London, “almost single-handedly is responsible for bringing AIG down and by reference the economy of this country”, says Jackie Speier, a US representative. “They basically took people’s hard-earned money, gambled it and lost everything. And he must be held accountable for the dereliction of his duty, and for the havoc he’s wrought on America. I don’t think the American people will be content, nor will I, until we hear the click of the handcuffs on his wrists.”

This account is as satisfying as it is easy to understand. It treats the blowing up of the world financial system like a global version of Barings, the bank that collapsed in 1995, with Cassano in the role of Nick Leeson. Operating from the fifth floor of a polished white stone building in Mayfair, Cassano’s unit sold billions of pounds of derivatives called credit-default swaps (CDS), allowing banks to buy risky debt without attracting the attention of regulators. AIG took the fees, but did not have the money to pay up if the loans went bad. By the time the music stopped, European banks had protected more than $300 billion of debt with this bogus “insurance”. And that is just one corner of a web of risk extending to over 1,500 big corporations, banks and hedge funds. In a 21-page paper known as the Mutually Assured Destruction memo, AIG claims that if the bailouts stop and the company is allowed to go bust, it will take the world with it. Cassano must have played with handcuffs as a child: he is the son of a Brooklyn cop. Now he waits for the fallout.

But the official version overlooks many things, including episodes of fraud at AIG that go back at least 15 years. It fails to explain why Public Enemy No 1 was allowed to leave the company on generous terms, with a retainer of $1m a month and up to $34m (£23m) in bonuses. And it does nothing to tell us why other big companies, whose profits looked as smooth and certain as AIG’s in the good times, are also fighting for survival.

When Forbes published its first list of the world’s biggest companies in 2004, AIG ranked third, after Citigroup, the dying bank, and General Electric, the industrial giant now drowning in its own debt. If you can think of a risk to insure, AIG was there: the company even made plans to survive a nuclear holocaust. It was built into a behemoth by one of the 20th century’s corporate titans, Hank Greenberg. Less famous than the other insurance legend, Warren Buffett, Greenberg gave shareholders a return of 14% a year, and was equally loved. “I just think you are the most stupendous, unbelievable person in the entire industry, the entire world,” one investor told an annual meeting, without irony.

und noch drei weitere Seiten brillant geschrieben

business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/...ffset=12&page=2

Alles wird gut!

One regulator tried to act on Bowsher’s warning, but she was silenced. Brooksley Born, who monitored the futures markets, tried to extend her remit to unregulated derivatives. Alan Greenspan and Robert Rubin, the then Treasury secretary, persuaded Congress to freeze her already limited power, forcing her departure. Rubin had come into government from Goldman Sachs; when he left he went back to banking, and pushed for Citigroup to step up its trading of risky, mortgage-related investments. For his advice, he earned over $126m (£84m) and then, as Citigroup collapsed, became an adviser to Barack Obama. After Greenspan stepped down from the US central bank in 2006, he became a consultant to Pimco, the world’s biggest bond fund, where his insights have been praised by his boss. “He’s made and saved billions of dollars for Pimco already,” said Bill Gross last year. Greenspan is also an adviser to Paulson & Co, a hedge-fund group that has made billions from the collapse in American housing.

The lightness of touch reached a level that defies belief. America has an Office of Risk Assessment, set up in 2004 to co-ordinate risk management for the main regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Jonathan Sokobin, its director, says it is charged with “understanding how financial markets are changing, to identify potential and existing risks at regulated and unregulated entities”. According to its website, it also helps to “anticipate, identify and manage risks, focusing on early identification of new or resurgent forms of fraud and illegal or questionable activities… across the corporate and financial sector”. By early 2008, this office was reduced to a staff of one. “When that gentleman would go home at night,” says Lynn Turner, the SEC’s former chief accountant, “he could turn the lights out. We had gotten down to just one person at the SEC responsible for identifying the risk at all the institutions.” The $596-trillion market in unregulated derivatives, including $58 trillion in credit-default swaps, was being watched by one person. That’s when he wasn’t looking at the rest of the corporate world, of course. ...........

One question has not been answered. Was Cassano’s team simply the dumbest in the room, betting on an ever-rising housing market against the likes of Goldman Sachs? Or was the world financial system brought down by fraud — a fraud made possible by the gradual but relentless takeover of public life by the insiders’ club of finance?

In 2001, with AIG trading at $85 on the New York Stock Exchange, The Economist decided to commission some research on the company’s true value, and chose the little-known firm Seabury Analytic to do it. This was deliberate. The magazine’s New York bureau chief, Tom Easton, had been around long enough to know that nobody on Wall Street ever says “sell”, except perhaps when a market is about to go up, and that the big security firms could not be trusted to give a candid view of AIG.

The research, which took five months, was the work of a team led by Tim Freestone, who is speaking here for the first time. Most analysts are upbeat: their colleagues’ bonuses depend on fees from the company under scrutiny. But Freestone’s firm (now called Crisis Economics) is independent. He judged that AIG was highly overvalued, and he would later realise that its shares were supported by an ability to stifle criticism. In his report for The Economist, however, he was tactful. To justify the share price, he said, “it would have to grow about 63% faster than [its] peers for the next 25 years. If investors believe that AIG can sustain this type of performance for that period of time, then AIG is properly valued”. Any investor who believed that would need to be certified.

After the article came out, researchers from the big banks contacted him, incredulous that he had dug deeper than the industry norm and dared to release the findings. They seemed to be in awe, and at the same time jealous; nobody breaks the rules like this — not without paying a price. A delegation from AIG arrived at his office and presented him with a letter that seemed to renounce the story and to condemn its distortion of his research. He was intrigued to see the author’s name at the end of the letter — why, it was his name, and the AIG contingent was awaiting his signature. The company also sent its executives on a private plane to The Economist headquarters in London to demand a retraction. Legal threats followed.

“I assumed AIG was attempting to railroad us out of business,” says Freestone, who did not sign. .......

business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/...ffset=12&page=2

Der weltweite Abschwung, in Tempo und Ausmaß, lässt die vorherige Weltwirtschaftskrise bis jetzt wie Kinderkacke erscheinen. Ich wage deshalb eine "gewagte" Aussage: Es wird in diesem Tempo nicht weiter abwärts gehen. Es wird sich stufenweise wesentlich verlangsamen und dabei wird es sogar minimale temporäre Erholungen geben. Ein Aufschwung ist das dann nicht, auch wenn es von vielen so interpretiert werden wird. Wie lange wir dann schlussendlich unten verweilen werden (der Boden wird auch nicht eben sein), ist jetzt noch nicht abschätzbar. Zuerst müssen wir unten ankommen.

Alles wird gut, fragt sich nur für wen?

Es bestehen starke Verdachtsmomente, dass Cassano keine unbedachte Fehlhandlungen begangen hat, sondern dass seine Handlungen, die letztlich zum Zusammenbruch von AIG geführt haben, von Wall Street Banken, insbesondere JPMorganChase, gesteuert waren, wobei jenen sicher keine Absicht unterstellt werden kann, den Untergang von AIG herbeizuführen, wohl aber maßlose Gier. Cassano war lediglich "Auftragsnehmer" für hoch riskante, jedoch lange Zeit sehr einträgliche Hebelgeschäfte.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Cassano

www.workerscompinsider.com/archives/000948.html

Und hier ein höchst fragwürdiges Dokument:

oversight.house.gov/documents/20081007102250.pdf

So say economists including Gregory Mankiw, former White House adviser, and Kenneth Rogoff, who was chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. They argue that a looser rein on inflation would make it easier for debt-strapped consumers and governments to meet their obligations. It might also help the economy by encouraging Americans to spend now rather than later when prices go up.

“I’m advocating 6 percent inflation for at least a couple of years,” says Rogoff, 56, who’s now a professor at Harvard University. “It would ameliorate the debt bomb and help us work through the deleveraging process.” Such a strategy would be risky. An outlook for higher prices could spook foreign investors and send the dollar careening lower. The challenge would be to prevent inflation from returning to the above-10-percent levels that prevailed in the 1970s and took almost a decade and a recession to cure.

“Anybody who has been a central banker wouldn’t want to see inflation expectations become unhinged,” says Marvin Goodfriend, a former official at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. “The Fed would have to create a recession to get its credibility back,” adds Goodfriend, now a professor at Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business in Pittsburgh.

For the moment, the Fed’s focus is on preventing deflation -- a potentially debilitating drop in prices and wages that makes debts harder to repay and encourages the postponement of purchases. The Labor Department reported May 15 that consumer prices were unchanged in April from the previous month and were down 0.7 percent from a year earlier.

“We are currently being very aggressive because we are trying to avoid” deflation, Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke told an Atlanta Fed conference on May 11. The central bank has cut short-term interest rates effectively to zero and engaged in what Bernanke calls “credit easing” to spur lending to consumers, small businesses and homebuyers.

www.kitco.com/ind/nadler/may192009A.html

Aber irgendwie traue ich dem Shortbraten immernoch noch nicht. Jetzt schnell down wäre zu einfach.

Ich habe ein paar Aktien auf der Agenda: MAN, SAP, BMW, ThyssenKrupp - all das sind Kandidaten für ein desaströses Jahr vom operativen Geschäft her. Index als allgemeiner Short-Trade ist mMn eher riskanter zu traden, da bei den Banken/Versicherungen extreme Ausschläge möglich sind. Bsp. Ackermann sagt, jetzt nicht mehr 25%, sondern 30% EK-Rendite ;-9

In den Ernst zu nehmenden Medien und Blogs dürfte man diesem "neuen" David Rosenberg starke Beachtung schenken.

Hier seine erste Analyse als "freier Mensch":

ems.gluskinsheff.net/Articles/...fast_with_Dave_051909_v5.pdf

Euch allen noch eine erfolgreiche Börsenwoche!

Uns ist die halbe Welt bekannt.

Doch gibt´s nur e i n Daheim.

--> www.vorkriegsgeschichte.de/ <--

Der Chart zeigt das charakteristische Muster einer i - v - Korrektur. Die massive schwarze Kerze am Zählpunkt von v bestätigt diese Sicht. Hat David Rosenberg diese Bank eventuell auch deswegen verlassen, weil er sie als stark gefährdet ansieht? Meines Wissens ist er auch ein exzellenter Charttechniker. Im übrigen kennt er ja sehr genau den "Klotz", den sich die BofA mit der Übernahme von Merrill ans Bein gebunden hat.

Japan's economy shrank a record 4.0 percent in the first quarter as companies slashed investment and exports but economists see a return to modest growth in coming quarters even as the longer-term outlook remains murky.

Recent signs of rebound in Japan's industrial production and some other global economic data have raised hopes that the world's second largest economy could post its first positive growth in April-June after four straight quarters of contraction to the end of March.

Still a recovery is likely to be fragile as thousands of jobs have been cut, dampening domestic consumption, and manufacturers worry that they may have to cut more staff and close more factories if the global recovery proves weak.

"The deterioration in domestic demand has just started. But external demand probably hit bottom in the first quarter. Both exports and output are expected to rise in April-June. So I'd expect positive growth in the current quarter, said Hiroshi Watanabe, senior economist at Daiwa Institute of Research.

"From July-September, stimulus packages will boost growth, so I expect the economy to continue recovering mildly for the rest of the year."

The fall in gross domestic product (GDP), the biggest in records going back half a century, was smaller than the 4.2 percent drop expected by economists and followed a similarly bleak revised 3.8 percent contraction in the previous three months.

The yen tracked slightly higher after the data, to 96.07 per dollar while the Nikkei share average edged up 0.6 percent with the data in line with expectations.

Japan's contraction was much bigger than in other developped countries, because of its heavy dependence on export industries for growth, even as the global crisis has slashed demand for Japanese cars and technology.

The U.S economy, ground zero of the financial crisis, sank 1.6 percent in the first quarter (6.1 percent annualised) while the euro zone economy contracted 2.5 percent.

Falls in capital spending and exports was the main culprit behind Japan's large contraction, contributing to contraction of 1.6 and 1.4 percentage point respectively.

Exports are seen reversing in April-June, as the global economy has shown some signs of improvement, but there are doubts about whether this is a return to sustainable growth.

More from CNBC.com:

- BOJ Mulls Accepting Foreign Bonds as Collateral

- China Rolls Out Refineries, Light Industry Plans

- RBA: Australian Economy Unlikely to Bounce Sharply

- More Asia Pacific News

"Weaker-than-expect figures for capex and private consumption suggest the negative impact from the export plunge is spreading to domestic demand," said Hiroshi Shiraishi, economist, BNP Paribas.

"As such, the Japanese economy may return to growth temporarily but it could

suffer a contraction again afterwards." If the rebounds in output only reflect restocking after sharp inventory adjustments, that does not bode well for the export-driven Japanese economy, as domestic consumption is seen shackled by structural factors such as an ageing

population.

Die relativ hohe Differenz zwischen dem Schlusskurs von 11,25 Dollar und dem Ausgabekurs für die 2. Tranche zu 10 Dollar dürfte im heutigen Handel zu weiterer Kursschwäche führen, meint das WSJ (unten).

Der ursprünglich per Stresstest ermittelte Kapitalbedarf lag bei 50 Mrd., wurde von darüber "verärgerten" BAC-Managern jedoch auf 34 Mrd. "runtergehandelt". Da die Stresstest-Bedingungen aber eh zu weich waren (die "Stress"-AL-Quote von 8,9 % in 2009 wurde bereits erreicht!), ist damit zu rechnen, dass der tatsächliche Kapitalbedarf wohl doch eher bei 50 Mrd. oder gar deutlich darüber liegen wird. Wenn der BAC-Kurs weiter fällt, werden KEs zu Marktkonditionen immer schwieriger. Dann würde immer wahrscheinlicher, dass die "preferred shares" (Hybridkapital) der Regierung aus dem TARP-Programm zusätzlich in common shares (normale Aktien) umgewandelt werden. Damit droht weitere deutliche Kursverwässerung. Der in den letzten Tagen gefallene Kurs (siehe Chart in # 43343) nimmt diese Erwartung offenbar bereits vorweg.

BAC ist eine der wichtigsten Bank-Aktien in USA. Sollte sie weiter schwächeln, dürfte auch das Umfeld (Finanzaktien bzw. XLF) in Mitleidenschaft gezogen werden - und damit auch der SPX (Chart in # 43342)

WSJ

Bank of America Sells $13.5 Billion of Stock

By DAN FITZPATRICK

Bank of America Corp. has raised $13.5 billion through common-stock sales, with more than half of the total coming on Tuesday, as it taps rising investor appetite for financial stocks.

The total issuance of 1.25 billion shares by BofA is part of a previously announced plan to create a $33.9 billion buffer to meet the U.S. government's stress-test requirements and fortify the bank against future losses as its loans and other assets are hit by the recession.

Combined with the bank's recent $7.3 billion sale of a stake in China Construction Bank, BofA has generated an infusion of $20.77 billion, putting it more than halfway to the U.S.-set goal and easing concerns that BofA would have to take more government capital or be nationalized.

The Charlotte, N.C., bank sold a block of 825 million shares for $10 apiece on Tuesday, according to people familiar with the situation. The price was below the stock's closing price of $11.25 in New York Stock Exchange composite trading, which will likely put downward pressure on the stock in Wednesday's trading.

BofA previously sold an additional 425 million shares. The sales began May 8, the day after federal officials disclosed stress-test results for the nation's 19 largest banks, including BofA. The average price of all the BofA share sales was $10.77, according to people familiar with the situation...

online.wsj.com/article/SB124277531733236861.html

The next financial meltdown will be in the currency markets, as central banks around the world have been printing money, giving the appearance of massive government intervention to weaken their currencies, legendary investor Jim Rogers, chairman, Rogers Holdings, told CNBC Wednesday.

"At the moment I have virtually no hedges, I suspect it is going to be the next problem, big crisis will be in the currency markets, I'm trying to figure out what to do there," Rogers told "Squawk Box Asia".

Rogers has bought the yen because he expects the Japanese currency to withstand future problems, but he does not have short positions in any currency and is currently not buying the yen any more.

"I'm certainly not short in the dollar — not at the moment, although it may be the peak. We may have come to the peak," he said. "I don't plan to own the yen forever, because you know the Japanese, Japan has some huge problems down the road."

For the moment currencies may look safer than anything else in the markets, as stocks may face a new bottom since they were artificially lifted by the amount of money created by central banks, but there are pitfalls ahead, he said.

"If I am right, you're going to see a lot of currency problems in the next decade or two," Rogers said.

"Governments around the world are doing their best to destroy currencies, many currencies in fact. And people need to understand that; if they don't understand it now, they're going to find out, they're going to find out the hard way," he added.

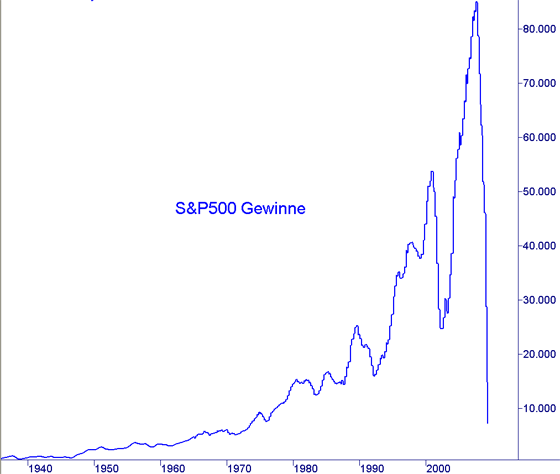

Aktuelle Gewinnsituation der 500 US-Unternehmen, die im S&P500 gelistet sind

Das sich daraus ergebene Kurs-Gewinn-Verhältnis (KGV)

|

Passende Knock-Outs auf DAX

| Strategie | Hebel | |||

| Steigender DAX-Kurs | 5,00 | 10,03 | 19,97 | |

| Fallender DAX-Kurs | 5,44 | 9,99 | 19,99 | |

Neueste Beiträge aus dem S&P 500 Forum

| Wertung | Antworten | Thema | Verfasser | letzter Verfasser | letzter Beitrag | |

| 56 | PROLOGIS SBI (WKN: 892900) / NYSE | 0815ax | Lesanto | 06.01.26 14:14 | ||

| 469 | 156.447 | Der USA Bären-Thread | Anti Lemming | ARIVA.DE | 04.01.26 10:00 | |

| 29 | 3.795 | Banken & Finanzen in unserer Weltzone | lars_3 | youmake222 | 02.01.26 11:22 | |

| Daytrading 15.05.2024 | ARIVA.DE | 15.05.24 00:02 | ||||

| Daytrading 14.05.2024 | ARIVA.DE | 14.05.24 00:02 |